Without an examination of the Kurds' role in the region, it is impossible to comprehend the rapidly evolving geopolitical dynamics of the Middl

February 9 and 11: Kashmir’s Unfinished Tragedy. By Dr. Ghulam Nabi Fai, Chairman, World, Forum for Peace & Justice

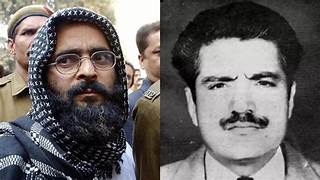

Every year, February 9 and February 11 are observed in Kashmir and across the Kashmiri diaspora as days of mourning. They mark the executions of two men whose lives and deaths have come to symbolize a much larger tragedy—Muhammad Afzal Guru, hanged on February 9, 2013, and Mohammad Maqbool Bhat, executed on February 11, 1984. These were not ordinary executions. They were political acts carried out in the shadow of an unresolved conflict that continues to haunt South Asia and the international community.

Afzal Guru was sent to the gallows, in the words of India’s Supreme Court, to satisfy the “collective conscience of society,” despite the Court’s own admission that there was no direct evidence linking him to the crime for which he was convicted. His execution was carried out in secrecy; his family was not informed in time, and his body was buried inside the high walls of Tihar Jail. Supreme Court advocate Kamini Jaiswal later described the hanging as a “political decision,” executed hastily and covertly for political mileage.

Nearly three decades earlier, Mohammad Maqbool Bhat met a similar fate. Executed for opposing India’s control over Kashmir, he too was denied the dignity of burial in his homeland. To this day, both men remain buried within prison grounds—an enduring symbol of unresolved injustice.

The parallels between the two are striking. Both men hailed from villages in Sopore, in the Kashmir Valley, just a few miles apart. Both were executed in the month of February, only two days apart on the calendar, though in different years. And both came to represent, in different ways, the Kashmiri demand for dignity, justice, and self-determination.

Maqbool Bhat occupies a unique place in Kashmir’s political memory. He was not merely a symbol of resistance but a man of ideas, clarity, and conviction. He believed—without ambiguity—that the only durable solution to the Kashmir dispute lay in an independent and democratic Jammu and Kashmir, based on the will and consent of its people. Even Sunil Gupta, former Public Relations Officer of Tihar Jail, acknowledged in his memoir Black Warrant that Maqbool Bhat repeatedly described himself as a political prisoner who stood for an independent Kashmir.

On the eve of his execution, Maqbool Bhat recorded a will in which he famously declared: “There will be many Maqbool Bhats who will come and go, but the freedom struggle in Kashmir should continue.” History has proven him tragically prescient. Decades later, the conflict remains unresolved, and generations of Kashmiris continue to live under militarization, political uncertainty, and recurring cycles of repression.

Bhat’s words resonate because they reflect a deeper truth about struggles for freedom. “It is easy to talk about freedom,” he once observed, “but it takes far more courage and patience to fight for it.” He understood that such struggles test not only resolve but friendships, loyalties, and moral endurance.

That legacy is visible today in figures such as Mohammad Yasin Malik, a prominent Kashmiri political leader currently imprisoned in Tihar Jail. Malik’s decision to pursue a nonviolent and democratic path distinguished him internationally and earned him recognition far beyond South Asia. Yet he too faces what many observers consider a deeply flawed and politically motivated prosecution, aimed less at justice than at silencing dissent.

The execution of Afzal Guru further exposed the fragility of democratic claims in the face of political expediency. As writer Arundhati Roy observed, Guru’s tragedy cannot be understood in isolation from Kashmir itself—one of the most heavily militarized regions in the world, where extraordinary security measures coexist uneasily with assertions of democracy and rule of law. What set Guru’s execution apart, Roy argued, was that it unfolded in full public view, with every major institution of the state participating in the process.

Amnesty International condemned the execution as a disturbing regression toward secrecy and state violence.

Veteran Kashmiri leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani described Mohammad Maqbool Bhat as “the national hero of Kashmir who was a source of inspiration for us and that the people of Kashmir are proud of him,” emphasizing that the greatest tribute to him is to ensure that the people of Kashmir never forget his sacrifice. He also termed Afzal Guru’s execution a “judicial murder,” stating that public sentiment cannot replace due process or legal sanctity.

More than forty years after Maqbool Bhat’s execution, and more than a decade after Afzal Guru’s, the Kashmir dispute remains unresolved. The denial of their bodies to their families reflects not closure, but fear—fear of memory, fear of symbolism, fear of unresolved truth.

February 9 and February 11 are not only days of mourning. They are reminders—of justice deferred, of voices silenced, and of a conflict the world has grown accustomed to ignoring. Remembering Maqbool Bhat and Afzal Guru is not about glorifying death; it is about confronting uncomfortable questions of law, morality, and political responsibility.

Until those questions are addressed honestly, Kashmir’s tragedy will remain unfinished—and its Februarys will continue to mourn.

(World Kashmir Awareness forum. He can be reached at: WhatsApp: 1-202-607-6435 gnfai2003@yahoo.com) www.kashmirawareness.org

Afzal Guru was sent to the gallows, in the words of India’s Supreme Court, to satisfy the “collective conscience of society,” despite the Court’s own admission that there was no direct evidence linking him to the crime for which he was convicted. His execution was carried out in secrecy; his family was not informed in time, and his body was buried inside the high walls of Tihar Jail. Supreme Court advocate Kamini Jaiswal later described the hanging as a “political decision,” executed hastily and covertly for political mileage.

Nearly three decades earlier, Mohammad Maqbool Bhat met a similar fate. Executed for opposing India’s control over Kashmir, he too was denied the dignity of burial in his homeland. To this day, both men remain buried within prison grounds—an enduring symbol of unresolved injustice.

The parallels between the two are striking. Both men hailed from villages in Sopore, in the Kashmir Valley, just a few miles apart. Both were executed in the month of February, only two days apart on the calendar, though in different years. And both came to represent, in different ways, the Kashmiri demand for dignity, justice, and self-determination.

Maqbool Bhat occupies a unique place in Kashmir’s political memory. He was not merely a symbol of resistance but a man of ideas, clarity, and conviction. He believed—without ambiguity—that the only durable solution to the Kashmir dispute lay in an independent and democratic Jammu and Kashmir, based on the will and consent of its people. Even Sunil Gupta, former Public Relations Officer of Tihar Jail, acknowledged in his memoir Black Warrant that Maqbool Bhat repeatedly described himself as a political prisoner who stood for an independent Kashmir.

On the eve of his execution, Maqbool Bhat recorded a will in which he famously declared: “There will be many Maqbool Bhats who will come and go, but the freedom struggle in Kashmir should continue.” History has proven him tragically prescient. Decades later, the conflict remains unresolved, and generations of Kashmiris continue to live under militarization, political uncertainty, and recurring cycles of repression.

Bhat’s words resonate because they reflect a deeper truth about struggles for freedom. “It is easy to talk about freedom,” he once observed, “but it takes far more courage and patience to fight for it.” He understood that such struggles test not only resolve but friendships, loyalties, and moral endurance.

That legacy is visible today in figures such as Mohammad Yasin Malik, a prominent Kashmiri political leader currently imprisoned in Tihar Jail. Malik’s decision to pursue a nonviolent and democratic path distinguished him internationally and earned him recognition far beyond South Asia. Yet he too faces what many observers consider a deeply flawed and politically motivated prosecution, aimed less at justice than at silencing dissent.

The execution of Afzal Guru further exposed the fragility of democratic claims in the face of political expediency. As writer Arundhati Roy observed, Guru’s tragedy cannot be understood in isolation from Kashmir itself—one of the most heavily militarized regions in the world, where extraordinary security measures coexist uneasily with assertions of democracy and rule of law. What set Guru’s execution apart, Roy argued, was that it unfolded in full public view, with every major institution of the state participating in the process.

Amnesty International condemned the execution as a disturbing regression toward secrecy and state violence.

Veteran Kashmiri leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani described Mohammad Maqbool Bhat as “the national hero of Kashmir who was a source of inspiration for us and that the people of Kashmir are proud of him,” emphasizing that the greatest tribute to him is to ensure that the people of Kashmir never forget his sacrifice. He also termed Afzal Guru’s execution a “judicial murder,” stating that public sentiment cannot replace due process or legal sanctity.

More than forty years after Maqbool Bhat’s execution, and more than a decade after Afzal Guru’s, the Kashmir dispute remains unresolved. The denial of their bodies to their families reflects not closure, but fear—fear of memory, fear of symbolism, fear of unresolved truth.

February 9 and February 11 are not only days of mourning. They are reminders—of justice deferred, of voices silenced, and of a conflict the world has grown accustomed to ignoring. Remembering Maqbool Bhat and Afzal Guru is not about glorifying death; it is about confronting uncomfortable questions of law, morality, and political responsibility.

Until those questions are addressed honestly, Kashmir’s tragedy will remain unfinished—and its Februarys will continue to mourn.

(World Kashmir Awareness forum. He can be reached at: WhatsApp: 1-202-607-6435 gnfai2003@yahoo.com) www.kashmirawareness.org

You May Also Like

Pakistan was envisioned as a homeland where citizenship would not be determined by faith. Yet, more than seven decades later, that founding promise

Accountability is critical when it comes to ensuring that promises made by the governments translate into ground realities “where no one is l

"Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" By Nazir S Bhatti

On demand of our readers, I have decided to release E-Book version of "Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" on website of PCP which can also be viewed on website of Pakistan Christian Congress www.pakistanchristiancongress.org . You can read chapter wise by clicking tab on left handside of PDF format of E-Book.